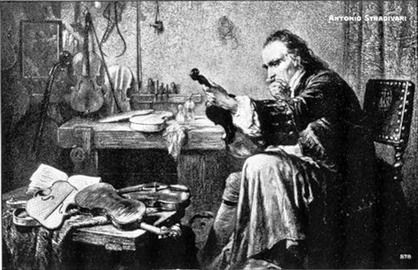

The luthiers of Cremona

The most famous violin maker of all time was undoubtedly Antonio Stradivari. What is less well know is that there was a whole group of luthiers living in Cremona at the same time, of which Stradivarius was the most successful.

These days, a Stradivarius instrument can command enormous sums of money, but it's not just his instruments that are so highly prized. Whole dynasties of instrument makers seemed to spring up in Cremona during the end of the seventeenth century, and the beginning of the eighteenth. One such family was the Guarneri, who lived just a few doors away from the Stradivarius, near the Piazza San Marco.

It is easy to imagine the envy and jealousy of the other luthiers when they saw their successful neighbour, with his rich and powerful customers bestowing their favours (and cash) in return for a genuine Stradivarius instrument. With Stradivarius dominating the market of kings and princes, the Medici, the church, the others were forced to sell their instruments to anyone who would pay - itinerant musicians, travelling players - none of whom had anything like the resources to buy one of Stradivarius's creations.

The Guarneri family was clearly overshadowed by Stradivarius. The impossibility of competing with Stradivarius inevitably set up tensions within the family, and the eldest brother, Pietro, left to set up his own business in Venice. The younger son remained, but it takes little imagination to feel the pressure

It was this background that convinced me that I could use one of the Guarneri family as a main character at the start of the book. And the ideal member was Giuseppe (also known as Bartolomeo), the son that stayed at home, and remained under the thumb of his father. Meanwhile, a few doors away, there were tensions too within the Stradivarius family. None of the children from Stradivarius' first marriage were able to come up to the level of their father, and the eldest, Omobono, also decided to leave home to escape the dominating influence of his father. However, he was forced back because of his mother's final illness. Stradivarius had eleven children in total, and it would be unthinkable that the Guarneri family did not know their neighbours. In particular, Stradivarius' daughter by his second marriage was called Francesca, and I found that according to most accounts she 'died' at the age of twenty. However, other accounts have her present at the death of her father some twenty years later than this. Amazingly for me, it also seems that she entered a nunnery at a most convenient point for my story. I decided that Giuseppe Guarneri (later known as Del Gesu) would display his ambition to rise above his father's relatively poor livelihood by marrying into the Stradivarius family, and by doing so, displace the great man;s sons as the natural successor to the Stradivarius name and business. The obvious way for him to do this was to marry Francesca.

Giuseppe Guarneri is reputed to have had weaknesses for both wine and women, and finally married - not Francesca Stradivari - but Katarina Rota, an Austrian. I decided that the Creponi mentioned at Richard Charke's arrival in Jamaica, should be the step brother of Katarina Rota, and that the reason for Guarneri to give the flawed violin to Creponi was the result of his being blackmailed over the affair with Katarina, and the fact that Francesca was already pregnant by him.

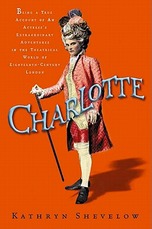

Charlotte Charke - my debt to Kathryn Shevelow

The family of Colley Cibber is a fertile ground for any author. Apart from his own outrageous story, the equally unbelievable history of his son, Theophilus, and his two marriages could keep me writing for years (and probably will!) - but more about Theo at a later date.

Just about everything I learned about Cibber's daughter, Charlotte, came from the research and writing of Kathryn Shevelow. Kathryn is a professor at the University of California, specialising in eighteenth-century British literature and culture.

It was her book, entitled 'Charlotte: The True Story of Scandal and Spectacle in Georgian London', that inspired me to write my full-length play 'Travesti', as well as to feature Charlotte, and her wayward husband, Richard Charke, in the novel, 'Scartato'.

I recommend this book to anyone wanting an accessible and fascinating way into the world of the theatre in the first half of the eighteenth century, and in particular, into the life of this truly original actress.

Thank you, Kathryn.

Travesty

Colley Cibber was the most famous and glittering theatrical figure of early eighteenth century London. At the height of his powers, as an actor, a dramatist, and theatre manager, he was a major celebrity. His name was on everyone’s lips, celebrated in every broadsheet in the capital. Like Lord Foppington, his most famous theatrical creation, he would dress in sublime, over-the-top Georgian splendour. It is said that Foppington’s wig was so large and magnificent that it had to be carried around in its own sedan chair.

Cibber himself was the target of every joke and ribaldry in the Town, and yet he was indescribably popular. But not universally so; the intellectual minority, overwhelmingly Tory, hated his effortless popularity, his over-weaning confidence, and despised his self-seeking vanity and sycophancy – and of course his Whig politics. He, on the other hand, cared nothing for their barbs and stings; he knew he was a success – and on which side his bread was buttered.

But while this dazzling dandy was flaunting his worldly success, gliding effortlessly among the great and the good, en route to becoming the most untalented Poet Laureate in history, his youngest daughter and her small child were starving to death in the streets of London.

What brought about this schism between Cibber and his daughter Charlotte? Was it her penchant for playing male travesti roles on stage? Her theatrical cross-dressing spilling over into her private life? Her biting satirical parodies of her own father’s famous stage roles? Her refusal to bow down to the sexual conventions of the day? Or was she merely a pawn, sacrificed in a larger game of politics, which resulted in two hundred years of censorship of the English stage?

One interpretation of this fascinating story is told in my play, Travesti, which you can read here.

Although largely forgotten today, Colley Cibber stood out in the theatre of the early eighteenth century. Rising from apprentice actor to become (like David Garrick some 30 years later) actor-manager in charge of Drury Lane, Cibber was actor, author, playwright and celebrity. Through his ability to flatter and ingratiate himself with the rich and powerful, Cibber eventually rose to become Poet Laureate. But his talents for hypocrisy and self-promotion were never inherited by his youngest daughter, Charlotte, who despite following in her father’s theatrical footsteps, insisted on ploughing her own furrow, and flying in the face of his conventional sensibilities.

Charlotte became notorious not only for playing male travesti parts on the stage, but for carrying her cross-dressing into her private life. Suspicions about her immoral behaviour, together with her increasingly flagrant parodies of her famous father, led Cibber to disown her. Cut off from her chosen profession, and the love and support of a family, Charlotte (with her daughter Kitty) was condemned to a hand to mouth existence for the rest of her life, and eventually died in poverty.

The comic and tragic events of Charlotte's life - her defiance of convention in the face of her father's embarrassment and anger, and her inevitable fall from his favour - were played out against a sometimes surreal and distinctly non-contemporary picture of the eighteenth century. When prevented from appearing on the London stage by the machinations of her powerful father and his political friends, Charlotte resorted to running a puppet theatre, which continued to satirise the powerful figures of the day (including her father). When this failed, she became by turns a shopkeeper, a pie maker, a gardner - in fact anything that would save her and her daughter from starvation.

Her downfall may be seen to have started with her unfortunate marriage to the lead violinist of the Drury Lane orchestra, Richard Charke. Charke was ruthlessly ambitious, and saw Charlotte as the route to her father's favours and fortune. Aged seventeen, she fell in love with the romantic musician, and they were married. In doing so, Charlotte became Richard Charke's 'property', and all her income from her stage performances became his. Sadly, her money was not sufficient to pay for Charke's licentious lifestyle of gambling and womanising, and (it is said) having sold her valuable stage costumes to pay yet another gambling debt, he left her and his young daughter, Kitty.

Charke's excesses couldn't last, and he eventually decided to flee from his creditors, and his latest lover, to the safety of the West Indies. His arrival there was recorded in the book, 'Revels in Jamaica' by Richardson Wright as follows:

'In 1735, Henry Moore, later to become Lieutenant Governor of Jamaica and Governor of New York, arrived home. A native of the island, being born at Vere, he was sent abroad to be educated. After studying at Leyden, he took the usual grand tour, travelled though France, Italy and a considerable part of Germany. To Jamaica he brought with him a band of musical performers, the principal of whom were the famous Richard Charke, Colley Cibber’s son-in-law, and an Italian named Creponi.'

And, even though I didn't know it at the time, that was the starting point for the story of Scartato.

Where did the idea come from?

If you've read the About the Author page, you'll have noticed that I'm currently writing a second version of The Beggar's Opera! Now two adaptations of the same play might sound like a bit of overkill, but I've had a very long history with that show, which started way back when I was in university.

I discovered John Gay's masterpiece by accident one afternoon when I was looking through scores at South Woodford library to get ideas for which show the Queen May College Light Opera Society could perform next. I realised very quickly that I would need to adapt the original (1728) version for modern tastes, but the vitality and realism of the cast of characters was such that it instantly seemed modern (in my imagination, at least). To cut a long story very short indeed, I rewrote the show and we performed it in modern dress, with completely revamped music a year later.

Thirty years or so later, I played a part in a production of A Chorus of Disapproval, by Alan Ayckbourn, which uses the Beggar's Opera as a vehicle within the play. I was the only person to know the original, and it fell to me to arrange and teach the remainder of the cast the music for the excerpts used in the play. I remembered then how well the Beggar's Opera had worked when we put it on in London, and as I had just published my adaptation of A Savoy Christmas Carol using the music of Arthur Sullivan, I realised that I could do the same with the Beggar's Opera.

So, I created my first adaptation of the show, called The Savoy Beggar's Opera. It was intended to perform the piece in the Summer of 2012, but various difficulties got in the way - the rehearsal period proved to be too short for the scale of the piece, and summer holidays and other commitments prevented us from finding a complete cast (in particular a chorus who could do justice to Sullivan's music). So we cancelled.

I was determined that we should put the show on, as it contains such a wealth of wonderful characters, and, as a political satire, was as relevant today as it was in the eighteenth century. I'm not the only person to think that - Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weil adapted it to create the Threepenny Opera in 1928 (remember Mack the Knife?). So, I decided that we would create a new adaptation, this time without the necessity for 4-part chorus in order to cut down the rehearsal time, and reduce the requirement for so many people.

So much for my obsession with the Beggar's Opera! But it doesn't tell you where the idea for the book came from...

While I was researching the Beggar's Opera, I found out that prior to its amazing success at the Haymarket Theatre in 1728, it had been turned down by the Drury Lane Theatre. Of course, the term 'amazing success' is relative - it ran for sixty-nine nights - but this should be compared with the usual run of theatrical performances in those days, which were lucky to reach their third night (on which the author got paid!). So sixty-nine was equivalent to the run of Phantom of the Opera or Les Miserables in our day.

So who made the disastrous mistake of turning down the Beggar's Opera (equivalent to a publisher's rejecting the Harry Potter books, these days!)? His name was Colley Cibber, and he was one of the three partners who held the license to run the Drury Lane Theatre.

It was when I started to read about Colley Cibber, and his amazingly dysfunctional family, that the idea for the book hit me. But more about that in my next post...